More speed, more insight

By Jens Medler, Rohde & Schwarz, Test and Measurement Division, Munich, Germany

Friday, 02 August, 2013

FFT-based EMI test receivers used for compliance measurements can reduce scan time by several orders of magnitude and to provide more precise and reproducible measurements.

Traditional EMI test receivers measure a signal within the IF bandwidth during the set measurement time. This results in a long scan time for the entire frequency range, as the measurement time per frequency point needs to be quite long in order to capture intermittent emissions. FFT-based receivers measure the emitted signals in frequency segments much wider than the IF bandwidth. The actual IF bandwidth is achieved via an FFT filter bank and a bank of weighting detectors. This approach offers the following benefits:

- The time needed for measurement of electromagnetic emissions is significantly reduced by approximately the number of filters used with the FFT filter bank plus the time needed by the test receiver to switch frequency. This reduces test time by up to several orders of magnitude without degradation of accuracy.

- Ability to apply longer measurement times, eg, for measuring intermittent signals.

- Makes enhanced measurement functions like spectrogram and spectrum in persistence mode applicable.

With the publication of Amendment 1 to the 3rd Edition of CISPR 16-1-1 in June 2010, FFT-based measuring instruments were introduced for EMI compliance measurements. The publication of the basic standard is a prerequisite for the method to be used by product standards. This is already the case for emission measurements of sound and television broadcast receivers and associated equipment (CISPR 13:2006) and for multimedia equipment (CISPR 32:2012). Product standards for lighting equipment (CISPR 15) and for automotive equipment (CISPR 25) will follow.

The selection of the measurement time using an FFT-based EMI test receiver needs attention when measuring broadband disturbance and intermittent signals. Furthermore, the use of RF preselection filters is highly recommended for maximum dynamic range and to avoid overload. This is particularly true for quasi-peak measurements of weak pulsed signals in the presence of high amplitude signals.

The concept behind CISPR 16-1-1

Currently, CISPR 16-1-1 uses a ‘black box approach’ to define specifications for measuring apparatus. This means that all stated specifications must be met by the measuring apparatus, independent of the selected implementation or technology, in order to be considered suitable for measurements in accordance with CISPR standards.

To reflect this approach, a new definition of the term ‘measuring receiver’ has been added in Amendment 1:2010-06 to CISPR 16-1-1:2010-01. It says: “instrument, such as a tunable voltmeter, an EMI receiver, a spectrum analyser or an FFT-based measuring instrument, with or without preselection, that meets the relevant parts of this standard”.

As a consequence an FFT-based measuring instrument that meets the requirements of CISPR 16-1-1:2010 and its Amendment 1:2010 can be used for EMI compliance measurements. Generally, this comprises the following parameters: input impedance, detectors, bandwidth, overload factor, VSWR, absolute sine-wave voltage accuracy, response to pulses, overall selectivity, intermodulation effects, receiver noise and screening.

In addition to the above general requirement, the FFT-based measuring instrument shall sample and evaluate the signal continuously during the measurement time. This is essential for capturing impulsive disturbance and intermittent signals. It disqualifies the use of digital storage oscilloscopes for EMI compliance measurements due to the existence of blind times.

How a basic standard comes into force

Basic standards come into force with dated or undated normative references in product standards:

- If the reference is undated, the latest edition of the standard shall apply.

- If the reference is dated, the specific edition of the basic standard shall apply.

CISPR 13:2006 (Ed. 4.2) has undated references to basic standard CISPR 16-1, whereas all other CISPR product standards and IEC generic standards for emission measurements have dated references - see Table 1.

Table 1.

Dated references to CISPR 16-1-1

| Product standard | Reference to CISPR 16-1-1 | Stability date |

|---|---|---|

| CISPR 11:2010 (Ed. 5.1) - product standard for industrial, scientific and medical equipment (ISM) | CISPR 16-1-1:2006 and its Amendments 1:2006 and 2:2007 | 2014 |

| CISPR 12:2009 (Ed. 6.1) - product standard for vehicles, boats and internal combustion engines (protection of off-board receivers) | CISPR 16-1-1:2006 | 2014 |

| CISPR 13:2009 (Ed. 5.0) - product standard for sound and television broadcast receivers and associated equipment | CISPR 16-1-1:2006 and its Amendments 1:2006 and 2:2007 | 2014 |

| CISPR 14-1:2011 (Ed. 5.2) - product standard for household appliances and electric tools | CISPR 16-1-1:2003 | 2014 |

| CISPR 15:2009 (Ed. 7.2) - product standard for electrical lighting and similar equipment | CISPR 16-1-1:2003 | 2013 |

| CISPR 22:2008 (Ed. 6.0) - product standard for information technology equipment (ITE) | CISPR 16-1-1:2006 and its Amendments 1:2006 and 2:2007 | 2017 |

| CISPR 25:2008 (Ed. 3.0) - product standard for vehicles, boats and internal combustion engines (protection of on-board receivers) | CISPR 16-1-1:2006 and its Amendments 1:2006 and 2:2007 | 2014 |

| CISPR 32:2012 (Ed. 1.0) - product standard for multimedia equipment | CISPR 16-1-1:2010 and its Amendment 1:2010 | 2015 |

| IEC 61000-6-3:2010 (Ed. 2.1) - generic standard for residential, commercial and light-industrial environments | CISPR 16-1-1:2010 | 2014 |

| IEC 61000-6-4:2010 (Ed. 2.1) - generic standard for industrial environments | CISPR 16-1-1:2010 | 2014 |

Therefore, the users of CISPR 13:2006 (Ed. 4.2) and CISPR 32:2012 (Ed. 1.0) can immediately employ an FFT-based measuring instrument for EMI compliance measurements if the instrument meets the requirements of CISPR 16-1-1:2010 and its Amendment 1:2010 (Ed. 3.1). The references in CISPR 15 will be updated in 2013.

All other product standards are more or less in maintenance freeze until 2014. CISPR 22 will not be amended any further and will be replaced by CISPR 32 in 2017. For this reason, pure FFT-based measuring instruments will still not be suitable for compliance measurements for quite a long time.

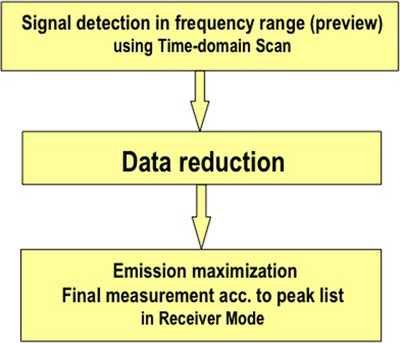

To gain from the dramatically increased measurement efficiency of FFT-based receiver technology it is beneficial to use an EMI test receiver, which combines the traditional EMI receiver concept with the FFT-based time-domain scan function in one device. Even if the product standard does not yet allow the FFT-based measurement, the method can be used for pre-qualification measurement followed by a measurement according to the traditional analog receiver method at the frequencies identified as critical (see Figure 1).

Timing and dynamic range considerations

Two different approaches for implementation of FFT-based receivers are possible:

- The oscilloscope approach digitising the RF signal directly using a high dynamic range AD converter.

- The receiver approach using a wideband IF design and digitising the IF signal.

The limitation with the oscilloscope approach is the AD converter, which needs to have a very high resolution and a high sampling rate to cope with the dynamic range requirements set by CISPR 16 and the bandwidth. Considering some margin for input filtering for a 1 GHz receiver, an AD converter with 2.5 GHz sampling rate is needed. To meet the CISPR 16 requirements, a minimum 14-bit resolution is necessary. Such AD converters are currently not available. Therefore, auto-range routines and software measures are necessary to get close to the required performance.

A better approach which guarantees the required performance is to combine both types in one instrument, eg, direct AD conversion up to 30 MHz input frequency and using, for example, a 30 MHz-wide IF with a traditional receiver concept. That way the bandwidth to digitise is limited to 30 MHz, putting lower and feasible demands on the AD converter.

This concept offers the following advantages:

- High dynamic range by limited bandwidth and availability of a high-resolution and high-dynamic 16-bit AD converter.

- The upper frequency limit of the receiver is not limited by the AD converter sampling frequency.

- The bandwidth filtering and all weighting detectors can operate in real time, ie, the complete conducted or radiated emission spectrum can be displayed without any interruptions or time gaps.

- Above 30 MHz the frequency range of interest is subdivided into several segments of, for example, 25 MHz, which are measured sequentially.

- Long maximum dwell time by low sampling rate, eg, up to 100 s.

- Thanks to the limited frequency band used for the FFT, an RF preselector can be used. It protects the receiver input from overload due to high out-of-band signals and guarantees correct measurement of weak disturbance signals in presence of strong signals.

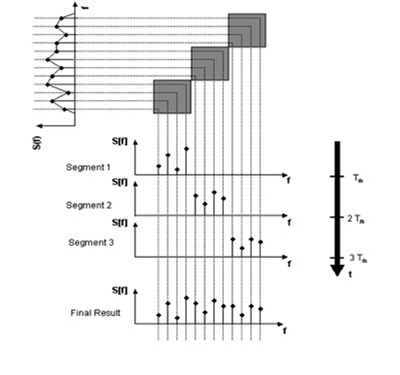

As a consequence, an FFT-based EMI test receiver combines a filter bank with N parallel filters and a stepped frequency scan using a step width according to the FFT width. For this purpose the frequency range of interest is divided into several segments that are measured sequentially (see Figure 2). The scan time Tscan is calculated as:

Tscan = Tm Nseg

where Tm is the measurement time for each segment and Nseg is the number of segments

For a correct measurement, the measurement time Tm is to be selected longer than the pulse repetition interval of impulsive noise. If the measurement time is too short, pulses are missed, which may result in enormous measurement result errors. In a worst case, the measuring receiver may not capture the disturbance signal at all. This is particularly fatal if the segment size has a large width, eg, 25 MHz or more.

If the pulse repetition interval is unknown, multiple scans with various measurement times using a ‘maximum hold’ function are necessary to determine the spectrum envelope. For low repetition impulsive signals, several (eg, 10 to 50) scans will be necessary to fill up the spectrum envelope of the broadband component. The correct measurement time can also be determined by increasing it until the difference between maximum hold and clear/write displays is below, for example, 2 dB.

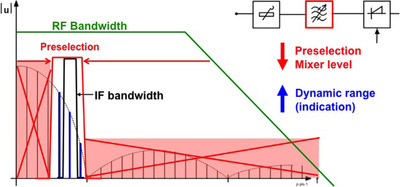

Generally the EMI test receiver must be equipped with preselection filters for providing a sufficient dynamic range for quasi-peak measurements of pulse signals with a low pulse repetition frequency (PRF), and particularly to protect the input circuit of the instrument from overload or damage when measuring weak disturbance signals in the presence of high amplitude signals or strong broadband signals with a bandwidth that is much wider than the instrument’s measurement bandwidth (see Figure 3).

A preselection filter of this type should provide at least 30 dB of attenuation at the frequency of the strong signal. A number of such filters are required to cover the frequency range 9 kHz to 6 GHz.

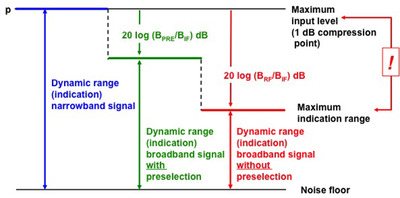

The dynamic range is limited on the bottom line by the displayed noise level at the requested resolution bandwidth, eg, 120 kHz in CISPR band 30 MHz to 1000 MHz. The upper limit is the 1 dB compression point of the first mixer. This maximum dynamic range can be used to measure a continuous-wave (CW) signal (narrowband) only. If a high-level broadband signal is measured, there will be very high levels of distortion products due to nonlinearities of the mixer.

As a consequence, the maximum intermodulation-free input level (maximum indication range) is reduced by the bandwidth factor (see Figure 4).

For example: The bandwidth factor without preselection is about 26 dB using an IF filter bandwidth BIF = 50 MHz, and assuming that the bandwidth of the broadband signal is equal to the RF bandwidth of the EMI test receiver BRF = 1 GHz. The bandwidth factor is about 6 dB using a preselection filter with a bandwidth BPRE = 100 MHz, hence the maximum indication range is 20 dB higher than without preselection.

Time-domain scan and persistence mode

Rohde & Schwarz has introduced a new generation of FFT-based EMI test receiver for CISPR 16 compliant disturbance measurements, the R&S ESR. Its FFT-based time-domain scan can deliver measurement speeds up to 6000 times faster than can be achieved with a traditional single-channel filtering approach.

Frequency scans in the CISPR bands using the peak detector can be performed in just a few milliseconds. And even with quasi-peak and average detector it takes just seconds, which makes preview measurements with peak detector obsolete. The fast measurement speed is particularly useful if the equipment under test can be operated only during a short period of time, eg, a starter motor in cars. A part of the time saving can also be used for applying longer measurement times in order to reliably detect narrowband intermittent signals or isolated pulses.

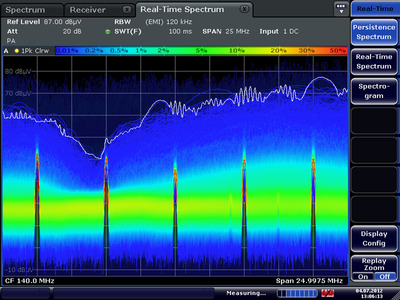

In persistence mode, the R&S ESR writes the seamless spectra into a single diagram (see Figure 5).

The colour of each pixel indicates how often a specific amplitude occurs at a specific frequency. Frequently occurring signals can be shown in red, for example, and sporadic ones in blue. If signals no longer occur at a specific frequency with a specific amplitude, the corresponding pixel disappears after a user-definable persistence period. This allows users to clearly distinguish between pulsed disturbances, which are present only for very brief periods, and continuous disturbances. In addition, different pulsed disturbances can easily be distinguished from one another.

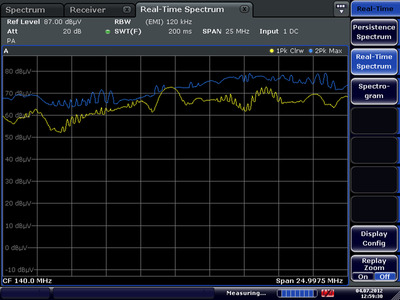

Example: The disturbance spectrum shown in Figure 5 is caused by an electric motor with poor EMI suppression. A second pulsed disturbance is clearly visible, which cannot be identified in conventional analyser mode as it is hidden by the broadband disturbance (see Figure 6).

Conclusions

FFT-based EMI test receivers can be used for EMI compliance measurements in accordance with Amendment 1 to the 3rd Edition of CISPR 16-1-1 if this standard is referenced in the product standard or if the reference is undated. Therefore, users of CISPR 13:2006 (Ed. 4.2) and CISPR 32:2012 (Ed. 1.0) can immediately employ an FFT-based measuring instrument for EMI compliance measurements. Users of other standards can use the fast time-domain scan to speed up the time-consuming preview measurements.

The use of FFT-based EMI test receivers is motivated by reducing the scan time by several orders of magnitude, and to get more insight due to the possibility for applying longer measurement times and enhanced measurement functions like spectrum in persistence mode. For precise and reproducible measurements the use of preselection filters is highly recommended.

Using AI to build your next-gen wireless system

The central challenge engineers face when designing wireless systems and networks is their...

Ensuring 5G network performance

To be successful in business-critical use cases, the wireless networks need to be as reliable as...

Ubiquitous connectivity is the future of wireless

Systems capable of seamlessly using satellite, cellular and local area networks are nowadays a...